Helping the Sun to Set on the King's Dominion

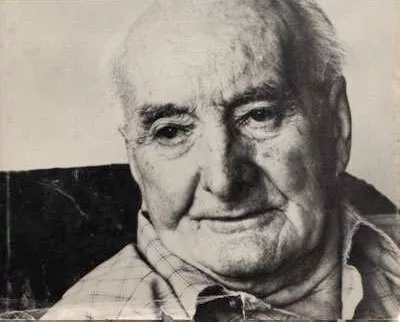

Denis Goulding was born February 4, 1893, in County Kerry, Ireland, in the small town of Knockanure, which means "hill of the yew tree". When he was sixteen, Denis joined the IRA, the Irish Republican Army, to fight for his country's independence from Britain. The Irish people had been ruled by Britain - against their will and often inhumanely - since the twelfth century.

For seventeen years Denis fought in the IRA, sometimes using guns, sometimes words, in what is called the Anglo-Irish War. He survived two hunger strikes and several years as a political prisoner. Although he himself was never injured, he saw many of his friends killed in warfare, tortured in prison, or executed.

Irish representatives finally signed a peace treaty with Britain in 1921, but they signed under Britain's threat of "immediate and terrible war". The treaty included a provision that called for the partition of Ireland into two countries: the Irish Free State, which later became the Republic of Ireland, and Northern Ireland. The Irish Free State, four-fifths of Ireland, would govern itself as a member of the British Commonwealth, but Northern Ireland would remain under British rule.

After the Anglo-Irish War and two years of civil war, Denis Goulding was released from prison, where he had spent fifty-two days on a hunger strike. He returned to Knockanure. Seeing his country divided, he was broken in heart and spirits ~ He felt he could do no more. Vowing never to return as long as the Union Jack (the British flag) was allowed to fly over any part of his homeland, Denis left Ireland.

On October 26, 1926, he arrived in the United States, where another struggle for independence from British rule had once been fought. He came to make a new home and is now an American citizen.

Denis follows closely the events in Northern Ireland. He passionately supports the IRA's current activities, which he views as a continuation of the struggle in which he participated a struggle for a free and unified Ireland. He has never returned to his native country.

It was very few people that wanted to accept the challenge to fight for Ireland's independence. I remember that I accepted that challenge because I was taught my country's history in a farmer's barn, one side of a hedgerow, by an Irishman who did love his country.

We weren't allowed to learn Irish history or geography in what they called the national schools - the regular schools controlled by the British. We had to learn it from the Hedge schoolmasters in underground schools, Hedge schools. It was very few parents that allowed their children to go to the Hedge schoolmaster for fear of the authorities of the town. They wanted peace. But it happened that my family didn't look at it that way. Generations before me had faced the same fight, the same problem. There are Irish families that have always fought for Ireland's independence down through the centuries. My family, the Goulding family, is among them. So they didn't object to any teacher teaching Irish history.

One time when we were going to the national schools, we learned that the sun never sets on the king's dominion, that is the British Empire. That was our education: The sun never sets on the king's dominion. Well, we were determined that it would set.

I joined the IRA, the Irish Republican Army, when I was, oh, about sixteen. At first our policy was passive resistance. We organized protest meetings. We got people out together the nearest town, no matter what the reason - a national celebration or whatever. And there is where you had speakers to protest the existence of an army of occupation in a land that didn't want them.

But we found out that we'd have to prove that we were ready to lay our lives down for what we wanted. And that's what drove us to obtain arms and to train ourselves in guerrilla warfare. That was not an easy job. We were all young, in our twenties at the very most.

I had many different jobs in the IRA, but for a time I was a captain, a staff captain. It was an awfully tiring life. We never had enough to eat; we never had enough sleep. Never. Not for months and months. But still we lived through it. We had very exciting times, very exciting times. My family never knew where I was, and neither did anybody else. I was just here today and gone next morning. And nobody knew where or when or what. It didn't profit anybody to know where you had gone and what you were doing.

We were a very closely knit army. There was no getting away from that fact. We didn't take any monkey business. If you talked loosely, you died. In the circumstances of that time, it was useless if you didn't have discipline, rigid discipline too many lives depended on it.

It was in the 1918 elections in the county of Waterford that we proved to Britain that we could defeat her at the ballot box. After years of passive and armed resistance, our political party - we were known as Republicans - had become Ireland's dominant party.

The son of an old Irish party man who had attended the British Parliament for many years was put up against one of our men, an IRA man, a Republican. The son was highly decorated from the First World War. He was a good man. He was a young fellow about our age. But he figured his daddy was right, and we figured we were right. We wanted to govern our land for ourselves.

We were never so tired in our lives. We spent twenty days without sleep, it seemed, or with very little sleep. Twenty- five of us - that's all that was there - went day and night from house to house. We told the people we could give them fair play, give them what they had wanted all their lives - freedom. We guaranteed that no Irishman would be conscripted into England's army again. 'Twas legwork all the way.

On the morning of October 26, 1918, the ballot booths were open for voting. And on the tops of the houses, behind chimneys, we saw machine guns for the first time. And British soldiers behind the guns. Huge posters were all over the place: "We're here to protect you so that you can go to the polls to vote." But they were really there to terrify the people, so that they would not go to the polls to vote.

And so we had to go from house to house in the early morning hours before daybreak and tell the people: "Don't go until we call for you. We'll send men for you. We'll take you to the polls."

We won hands down. Their man was badly defeated; our man was elected. Six weeks after that, in every part of Ireland - north, south, east, west - our men were elected. We won 73 of Ireland's 105 seats in the British Parliament in the 1918 elections. But instead of going to London to join the British Parliament, our representatives met in Dublin, Ireland. And on January 21, 1919, they declared Ireland an independent republic.

But the British government refused to recognize it as such. Warfare continued. And so our leadership, IRA leadership, decided to send about fifty of us over to Britain to tell the British people of our cause. We thought maybe they could influence their government to negotiate with us. I was one of those fifty young men.

We could go into any English pub, or tavern, and we'd have a crowd around us asking questions. Nobody was insulted when we got through, because they realized that we were telling the truth and that we had the guts to stand up for what we believed.

England, you see, wanted to keep Ireland as her kitchen garden - to supply cheap food to maintain her high industrial output. She discouraged the building of industrial plants in Ireland. For many years Ireland had raised and educated her children only to send them to England to glut the labor market. England wanted our cheap labor to keep her ships sailing to foreign ports with manufactured goods.

But after World War I, England began to feel pressure from her own people regarding her treatment of Ireland. Those of us who traveled around England helped in that. So in 1921 England's prime minister, Lloyd George - known as the Wizard of Wales - was forced to sue for a truce in Ireland.

Hostilities ceased. An Irish delegation was sent to London to arrange for the orderly removal of occupation forces and to agree on a just compensation for the destruction British forces had wrought in Ireland. But the Wizard had planned quite a surprise.

Lloyd George had written up his own dictation to the Irish people. He set up a boundary line across northeast Ireland and insisted that the six counties above the line would continue to be governed by England. He demanded British use of all Irish ports for a number of years and the completion of payments for lands we had taken back from English landlords. And he threatened "immediate and terrible war" if the Irish delegates did not sign this treaty.

The Irish people were divided over the treaty; the IRA was divided. The majority believed that even though the treaty called for a divided Ireland, the country could be reunited constitutionally within a couple of years. Those of us who knew Irish history knew that Britain would never permit it, but we were in the minority.

A choice had to be made at the polling booths: If the Irish people accepted the treaty without reservation, they would achieve a permanent peace, Lloyd George said; if not, immediate and terrible war. The delegates had no choice but to sign. The Irish people had no choice, either. No people ever voted for war, especially a war within their own borders.

We weren't getting our Ireland; we were getting only a part of Ireland, and a part of Ireland is no Ireland. Now, in the War of Independence here in the United States, what if the British government had demanded a fifth of the colonies? What would our answer have been? Well, that is what they demanded in Ireland: a fifth of a little fatherland that's only about the size of the state of Illinois.

My comrades and I, although we were a minority, refused to accept the partition. We knew we couldn't possibly win a war against England in a divided Ireland, but we wanted to protest with our own blood; we wanted a future generation fighting for the freedom of Northern Ireland to be able to tell the world that we never accepted the treaty.

So the next thing we had was civil war brother fighting brother. Divide and conquer - that's how Lloyd George thought he could win. But fifty years later we find the Irish Republican Army again denying England the right to rule in any part of Ireland.

The provisional government, the so-called Irish Free State government, passed a law imposing the death penalty on anyone carrying arms against that government. My life was in danger twenty-four hours a day. Nobody would have believed that the new government would dare to execute the very men who had fought so hard for Ireland's indepen- dence. But they did. They executed seventy-six of my comrades. Finally our commander in chief, Eamon de Valera, ordered us to lay down our arms and let ourselves be taken as prisoners.

And I was taken prisoner - a prisoner of the so-called Free State government. Let me tell you about prison. In a pitch-dark cell you don't hear a noise - not a twitter, not a sound. Oh, it is deadly, unless you sincerely believe in the justice of God and ask Him to help you.

There's such a thing in the Catholic Church as the fourteen Stations of the Cross. I don't know if you're acquainted with what they are. They commemorate the suffering that Christ endured on his way to Calvary from the hail where he was sentenced. Well, on that awful wall in my cell, I had all them stations mapped out in my imagination. I said them stations, and they gave me peace of mind. Nothing scared me. I didn't care what came along. That was the truth.

I spent fifty-two days on a hunger strike in Currah Military Camp in Kildare while I was a prisoner of the so-called Irish Free State. They said they'd turn us loose if we signed surrender papers stating that we wouldn't take up arms, and so on and so on and so on - give them our blessing if they wanted it - and so on. There were 1,400 of us; that's all. But we were determined that we'd die before we'd put our signatures to any paper of that kind.

I had decided what I would do and what I wouldn't do a long time before. I remember, oh, I guess maybe I was eight or nine years old. It was before the First World War about 1908, somewhere in there. Britain started releasing political prisoners from western Australia. That's where they had the salt mines, and that's where the Irish political prisoners slaved. There was one man, an Irish revolutionary hero, O'Donovan Rossa; he was a big man, but he was bent over. My dad put me on something so that I could see him coming up the street. The man had spent so many years laboring in the salt mines that his back got bent. He had a hard time raising his head to have a look at you.

Well, I remember at the time, and later, I made the remark that I wouldn't slave: I'd die. They'd have to kill me before I'd do it. I'd die of hunger; that's what I'd do. But they didn't conceive of a hunger strike in them days. Twas only in our times that we used the hunger strike. If you couldn't defend yourself in any other way, the hunger strike was the last resort.

Hunger is the cruelest weapon a man can use in his defense. The first three days are dreadful. Your body starts to use whatever fat is left on you, and your stomach seems to get disgusted with that. Although there is nothing in your stomach, you can't stop retching. And that goes on for maybe nine days. But from then on it isn't so bad. At least I didn't feel it was so bad. I could have stayed there forever. Course, I was slowly dying dying of starvation.

I remember when we were set free. An officer came in to me - I was in an isolation cell - and he says, "I'm glad it's over. You're free." Oh, no, I didn't pay any attention to him. I couldn't possibly believe that. Finally he went out and got a newspaper to show me.

Well, I was able to stand up and walk. But when they took me to a hospital, I looked in the mirror and saw that I was completely emaciated. The bones were just barely covered with skin. And, man oh man, we got the best treatment in the world. The nurses were hovering around us twenty-four hours a day. They were scared to death that somebody would die at the last minute.

No man can describe the feelings of dismay and depression that overwhelmed us after we were released from prison and saw our country partitioned, with a ten-foot high, double- row barbed wire fence with guard watchtowers along the line of separation.

At the time, the best of young Irish fellows, the cream of any land, left Ireland. But there were some who stayed behind, too; and from them comes whatever is working in the north of Ireland today. I believe that truly believe that. I'd like to be able to say that I'd stayed in Ireland to fight to the end to free all of Ireland. But I wanted to make my own living; I wanted peace just as well as anybody. I knew I wouldn't have it in Ireland because I knew that by nature I couldn't stay quiet.

So I came to this country about two years after my release, on October 26, 1926, with a girl who is now my wife of al- most forty years. We sailed on the steamship Franconia, and nine days later we landed in New York. I came to make a living and to have peaceable circumstances in which to make that living.

My future wife's sister, who had come to the United States about a year before, lived in Kansas City, Missouri; so we headed out there. Work was all-important, but it was hard to find. I worked that winter for a dairy farmer near Indepen- dence, Missouri, and the next spring I went to work in Kansas City for a small steel products company.

Labor unions were not effective in those days; men were hired and fired at will. I was lucky I didn't get fired. But work finally slacked down to two days a week.

About this time my future wife had gone to see some friends in St. Louis. She wrote back saying her friends thought they could find a better job for me there. So I quit my job in Kansas City and headed for St. Louis in 1927. But the job didn't materialize, and I spent anxious weeks walking and walking, following false rumors, and getting the same frus- trating reply - "You are not a citizen" - which I knew by then to be a patent evasion of the truth. The depression was starting then, and there just wasn't any work.

Finally, through acquaintances I found work in University City, a nice clean little suburb of St. Louis in St. Louis County. I belonged to a street repair gang. My wife, Kitty, and I were married about this time - April, 1928.

On the national scene, Herbert Hoover beat Al Smith for the presidency, and the Ford Motor Company electrified the whole country by declaring that its basic wage would be $4 for an eight-hour day about $25 for a six-day week. A four-room apartment, unheated, cost $25 a month. A job at Ford spelled "gold mine."

My brother-in-law worked at Ford at that time, and he believed he could get me a job. It meant good pay and no trouble with bad weather; so I quickly decided, yes, back to Kansas City again. But would you believe it? The day I disposed of our furniture and bought a bus ticket for Kansas City, a big bunch of workers, my brother-in-law included, were laid off from Ford. Four dollars a day gone.

President Hoover was not the culprit during our Great Depression. It wasn't until the banks closed down in 1929 that Congress finally believed that we were in a depression, even though millions of workers knew it at least one year earlier.

In 1935 Congress passed legislation called the Works Progress Administration, the WPA, which was designed to put people on public improvement jobs at pay decidedly lower than the prevailing industrial wage. I worked for WPA. Some of it was useful work. But some of it was degrading and humiliating work for men who wanted to work to earn a decent living.

By this time we were into President Roosevelt's regime, and Senator Wagner of New York wrote some very useful and badly needed social laws; but all those laws did not produce more employment. It was the Second World War and Hitler that sent us all to work men, women, and even children.

I came to Chicago in the fall of 1937 and went to work for the Chicago and Western Indiana Railroad as a night police- man protecting traffic at railroad crossings and guarding loaded freight cars from looters. Sometimes we had a little excitement, but generally it was monotonous work all night, ten hours a night, seven nights a week. During the shorter days of winter and early spring I seldom saw day- light. After four or five years of that, I went to work for the Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago as a maintenance engineer.

That's where I worked until 1964, when I retired at the age of seventy-one.

We thank our God and the people of the United States for the opportunity to make a fairly decent living and to raise a good family. Our firstborn, a girl, died in childbirth. We have three sons, one adopted, and they are all in managerial positions in the construction industry. We have fourteen grandchildren. Some have started in college. We hope they will contribute generously to the social structure of their native land.

I believe the most valuable product of any land is its youth. I saw what youth could do in my native land. Who would believe that generation after generation would shed their blood for the freedom of their country when the odds seemed impossible? But they did, and they did it gladly.

As a youth in Ireland, I was put through the mill. You'd be surprised at the ideas and the questions that come to you while you're in solitary confinement. You have plenty of time to meditate. And after some of my experiences in my adopted land, I have some questions. Why is it that today we have no money for useful employment, but tomorrow we have plenty of money for destruction? Why is it that municipalities all over our country have no money to pay their employees, while certain segments of our economy reap plentiful harvests? Why is it that humans have to scrounge in city slums in this country to find a living? What is it with our Congress? What is it with our money system?

I think that one of our biggest problems in this country is that we have deliberately robbed our children of the right to know and the duty to obey, through conscience, the laws of a supreme God. I believe that the myth of separation of church and state should be buried and that we should stop robbing our children of the most valuable ingredient in education a religious belief.

I have something else that I want to say. Not long ago the president of the Republic of Ireland spoke to the Congress of the United States to protest the aid that some Irish- Americans were sending his opposition in Ireland. His opposition, the Sinn Fein party an old and established party whose leaders have spent their lives and fortunes in the service of Ireland, especially a united Ireland immediately applied for visas to come to the U.S. to answer the charges against them. But they were refused.

You don't know the frustration and humiliation I felt as an Irish-American when my adopted land refused to admit representatives of my native land. I say to my adopted land, "You called Ireland your friend in 1776. What do you call her today?"

I am now an American citizen, but Ireland is still my native land. I have never gone back and probably never will. Let me tell you why. You might have heard the name Eamon de Valera. He was our president, Ireland's president, and my commander in chief for a time. He came to this country in, I think, about 1930. And all the guys who'd fought in the IRA, and who lived in the different cities of this country, tried to meet him. I did meet him. We were living in St. Louis at the time. He asked me to go back. I told him, impossible. I had vowed I wouldn't go back to Ireland as long as the Union Jack was allowed to fly over any part of my native land; no, because too many men that I knew died that it shouldn't fly there.

But I can tell you where I'd go if I were to visit Ireland. I'd go first to some little islands off the west coast of Ireland - the Aran Islands. That's where you'll meet the real Irish people and hear Gaelic, the real Irish language. Oh, it's beautiful there, the white sands and the beaches. The quiet- est place in the world.

In the evening you'll hear good music and eat good food. They have these sea birds that sleep in the crevices of the cliffs, and the natives capture them when they want to have a good feed. The birds are better than chicken. If you ever happened to visit there, you knew you were welcome, that was all.

That's where they make those wonderful woolen sweaters. In my time they had their own spinning machines and wove their own wool, pure virgin wool.

Those people were never bothered by the British. They lived on islands, see, and the British couldn't govern them. Yes, they are the real Irish; those people were always free.

(C) 1977 by Carol Ann Bales

Excerpted from the book: "Tales of the Elders" Published by Follett Chicago

| Additional Information | ||

|---|---|---|

| Date of Birth | 4th Feb 1893 | VIEW SOURCE |

| Date of Death | 15th Aug 1986 | VIEW SOURCE |